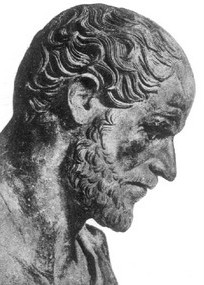

Class was great last night -- I enjoyed it. It was good (any dissenting opinions? No? C'mon, I know there is.). Nan commented that afterwards she felt like she had been recreating (as in recreation) -- and I must agree, the mental exercise pumped me up physically as if I had been using my muscles for more than Herman Göring impressions (Goering for all you Germanically impaired) or sticking my hand up Aristotle's dress.

But I have a problem. I want to accept Aristotle's words, but cannot at this point. I'll keep trying, and that's what this post is . . . an attempt to let you all get a little further into my head so you can figure out where I'm going astray.

I can totally agree with everything Aristotle has said to this point . . . everything. All that needs be done is birth me into the elite class. As long as I am elite, and there are rational reasons to maintain my natural born eliteness . . . I can agree with Aristotle on his whole scheme of virtues and vices.

Of course, looking at two vicious extremes is very much the way to find the good path . . . if you're elite. It gets a little harder when you're not . . . elite, that is. Y'see . . . if I'm elite, then somebody else has to be at the vicious extremes . . . and all along the spectrum of viciousness . . . for me to see and rationalize my path through the viciousness and onto the path of virtue, that leads ever upward to The Good. It certainly wouldn't do for me, an elite, to actually go out there and experience those vicious extremes . . . that's the job of the vulgar people -- those poor unfortunates who, try as they will, can never attain a life of virtue. It's their job to mark the path for the elites. The only reason an elite treads those vicious paths is through temporary ignorance.

"See, my brothers and sisters," saith one Elite to a magnificent assemblage of (male) humanity, "truely these lowborn are merely facsimiles of us. Their actions and desires are like unto the animals. Emotions toss their insignificant lives onto the rocks of vice so we can see the dangers therein. That is their purpose -- to show us where not to go. Let them flounder, it's what they do best. They would never be happy living our lives . . . they just don't understand. They can't comprehend. They don't realize!"

No way, José!

First of all . . . I do not claim high birth (though maybe, just maybe, in my wildest dreams, I'm related to that Edward, The Black Prince), nor do I claim an intellect as good as Aristotle or his colleagues. I am guilty of emotional excesses & rational deficiencies and rational excesses & emotional deficiencies, and will continue to have an abundance of emotional & rational escapades and rational & emotional lapses. I stand guilty of some of the most heinous of crimes, and have been duly punished (not as much as I should have been . . . but that's another story, one about Justice). I have hurt people; both those who deserved to be hurt and those who deserved naught but kindness from me. I can hurt you. Ain't nobody immune.

I reject any person's authority over me. I reject the notion that the elites are naturally sane and rational, and the unwashed masses are naturally handicapped in some way(s) mental, emotional, spiritual or physical. I reject the notion that animals are less than humans -- more correctly, I reject the notion that humans are more than animals. I reject a whole hell of a lot, actually. But I also accept a whole lot more than any group of elites will ever accept.

I accept that every human can be virtuous, and end up living a virtuous life even if they're crazy (Hey, Francis of Assisi, you really oughta stop flagellating yourself naked in the snow!). I accept that there are humans who are evil -- I've met a few, and the feeling (yes, Aristotle, FEELING, EMOTION) is immediately communicated, recognizable and palpable, undeniable and frightening. These evil people I have met have been the most coldly calculating, rational humans I have ever encountered. Do not make the mistake I speak of people without feelings . . . oh no . . . these evil people I've met certainly did have the full range of feelings we all have. That's the most scary part. You can see it all in their eyes (yes you can, Aristotle) as they take your measure, figure out what pleasure you can be to them, and weigh the enjoyment of your pain against possible consequences.

Evil.

Evil is real. Evil is in all of us.

I accept that even these most evil of people can find the virtuous human within them. Believe me, I've ran with gangs, lived in maximum/medium/minimum security prisons and met the whole range . . . on a personal and intimate long-term basis. I have wasted the days, weeks, months and even years away with winos, bums, schizophrenics, manic-depressives, obsessive-compulsives, anorexics, bulemics, common drunks, the shell-shocked and common & uncommon criminals, etcetera (even a catatonic . . . during my time in the nut house). I have counted among my friends: murderers, child molesters, rapists, bank robbers, muggers, gangbangers, women-beaters, gay bashers, felons & punks of all descriptions, prostitutes, drug dealers, pious religious fanatics and even a bona-fide Mafioso. I can count numerous victims of the above people (including the religious victims) as my friends as well. I have been both victim and perpetrator, perpetrator and victim. I have done bad things, even evil things -- and I knew what I was doing when I did them. I expect everybody knows when they are doing bad things -- don't give me no shit about involuntary or nonvoluntary actions, or even acting out of ignorance. That ain't it. That's an excuse for the elites. You know. Period.

Oh, in case anyone is worried . . . I have been punished (or excused) for all the crimes I have committed the state recognizes. I am not a wanted man. I have paid my debts to society . . . have you? Leave that be. This is philosophy here. Philosophy of the Ordinary Life.

Be honest -- you know, and actually decide and like, the things you do that are, shall we say, not exactly virtuous. Don't you? I do. Is anyone gonna say I am extraordinary? Pshaw! I am so pissin' ordinary you can hang a sign on me -- Typical Specimen of the Unwashed Masses. I've got the past to prove it. Ain't nowhere I hung around with anyone special, anyone better, anyone super, anyone worse, anyone different. I've seen a lot of humans, even a few born-elites up close and personal as friends, and all were readily recognizable by their actions as ordinary humans. None looked at me any differently. OK, maybe some did, but it wasn't with awe, I can tell you that much.

We all feel the same to me. Am I wrong?

If I'm right, then there is a way to reach everyone who is capable of performing the basic necessities of survival -- there is a way for each of us to find the path to a virtuous life. If there isn't . . . if virtue is just for the elite . . . I don't want no part of it. I like the people I've met in the unwashed masses. I understand them. I am one of them.

So . . . why does looking at two vicious extremes to find the virtuous mean unsettle me? Maybe because I've been out there on the extremes . . . and lemme tell ya, ain't no different from the mean. It's still about viciousness, not virtue. And besides . . . I found some of the best and goodest, kindest and caring, intelligent and wise, people suffering out there on the extremes of vice. I'll not leave them behind no matter what rules Aristotle or anyone else lays down . . . including your god.